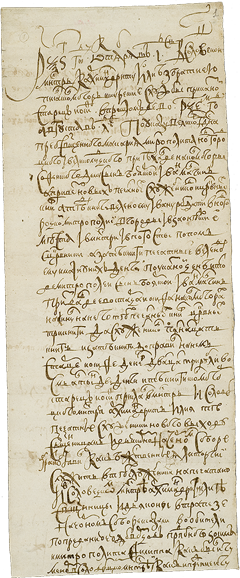

From Michael Romanov

to Peter the Great

The reign of Michael Romanov

When young Michael Romanov (1613–1645) was elected to the throne, he introduced a period of restoration with the help of his father Patriarch Filaret (1619–1633). The artistic legacy of the century of Ivan the Terrible was deliberately revived, doubtless to erase the memory of the Time of Troubles. Like his predecessors, Tsar Michael had the most significant relics brought to the Kremlin, and gave new impetus to the palace workshops. The new reliquary commissioned in 1628 by Michael I for Tsarevich Dmitry was therefore of symbolic importance.

The Stroganov workshops and painters

The Stroganovs were a family of merchants from the White Sea region. Their social ascent in the days of Ivan the Terrible and the first Romanovs stemmed from Russian expansion beyond the Ural Mountains and the colonization of Siberia. They were rewarded for their services with extensive properties in the newly annexed regions, where they set up commercial and industrial operations. The center of their empire was Solvychegodsk, on the Vychegda River, where they made their fortune from salt. In the late 16th century, the Stroganovs established an embroidery workshop there, which experienced its "golden age" around 1650-1680 under the direction of Anna Ivanovna, wife of Dmitry Andreevich Stroganov. A series of paintings, produced for them or under their patronage between the late 16th and late 17th centuries, came to be known as the "Stroganov school"; these were works by the finest artists of the tsar's workshops, such as Prokopy Chirin and Nazary Istomin-Savin. The "Stroganov school," distinguished by its precious nature and fragile slender figures, had a Mannerist elegance that gave it all its charm.

The contradictions of the 17th century

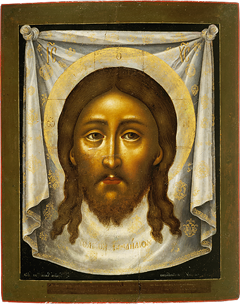

The reigns of Alexis Mikhailovich (1645–1676) and of his son Feodor (1676–1682) were marked by Russian expansion both westwards and eastwards to the Pacific (achieved in 1647). This period corresponded to a time of institutional change but of division too, with the schism of the Old Believers engendered by the reforms of Patriarch Nikon (1652–1658). At the same time, art forms slowly became westernized. The art of portraiture emerged, and the naturalism of Western painting began to influence the tsar's icon painters, first among whom was Simon Ushakov. Tradition and baroque innovation were sometimes surprisingly blended.

The revolution of Peter the Great

In 1697 and 1698, Peter I the Great (1682–1725) toured Europe on a diplomatic mission known as the "Grand Embassy" which marked a watershed between ancient and modern Russia. A gradual, tentative process of Westernization had begun in the mid-17th century, but Peter the Great imposed it nationwide with a series of radical reforms affecting army, state, and society. The Patriarchate itself—left without a head since the death of Patriarch Adrian in 1700—was abolished in 1721 and replaced with a state-controlled Holy Synod. Finally, St. Petersburg with its port on the Baltic was founded in 1703 and became the capital in 1712, consolidating Russia's orientation toward Europe. In the new city, domed churches were abandoned in favor of Western-style basilicas topped with spires. The Tsar sent for European architects and artists, especially from the Netherlands. Northern European baroque art flourished in St. Petersburg, and soon spread throughout Russia. Modern Russia was in the making.