The emergence of Moscow

(14th–15th century)

The emergence of Moscow

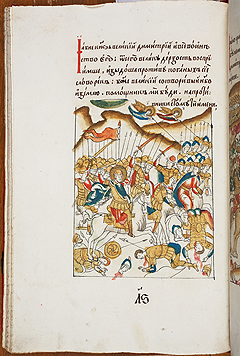

Moscow was first mentioned, almost in passing, in the chronicles of 1147; in the late 13th century, it became the capital of a small principality ruled by Prince Daniil, the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky. From 1304 to 1505, Daniil's descendants transformed the humble principality into a powerful state that gradually incorporated the other cities to become Muscovy, progressively freeing itself from the Tatar yoke. In 1380, the victory of Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy over the Tatars in Kulikovo was the first sign of this emergence from a domination that was to end a century later. In addition to the "gathering of Russian lands," the metropolitan see was decisively transferred from Vladimir to Moscow in 1328; the Russian church became independent of Constantinople in 1448. Finally, the revival of monasticism—initiated by St. Sergius of Radonezh in the mid-14th century and supported by the Grand Princes of Moscow—spread throughout Russia and soon reached the White Sea. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the rapid development of Moscow coincided with the work of Andrei Rublev and the influence of the gold and silver workshops of Photius, Metropolitan of Moscow (1408–1431). Moscow’s ties with Byzantium were reinforced, which influenced early Muscovite art to a greater or lesser degree.

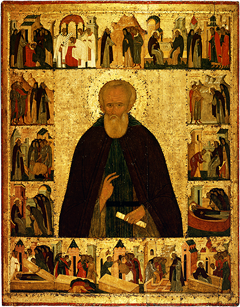

St. Sergius of Radonezh and the monastic revival

St. Sergius of Radonezh (1322–1392), founded the monastery of the Trinity when he was barely twenty years of age. He broke with the tradition of urban or suburban monasteries by founding his abbey in the forest wilderness, initiating a widespread movement of monastic colonization. The new, strictly disciplinarian communities soon became landowners, sometimes rising to the status of key players in the economic life of the country. With time, walled monastic cities came into being and began to play a significant artistic role. The movement spread far and wide. St. Cyril of Belozersk († 1427), a brother of the Simonov monastery in Moscow, headed north with his companion St. Ferapont († 1426); together they founded the family of monasteries on the White Lake (Belo ozero), giving their names to the two principal establishments. Hermitages and hamlets grew up along the banks of the rivers, ever further northward. The famous Solovetsky Monastery, on an island in the White Sea, was founded in two stages: at first, the monks Herman and Sabbatius († c. 1435) arrived on the island and lived there in solitude for a time; then a few decades later, Herman was joined by Zosimus († 1478), the true founder of the community, to whom Novgorod ceded the island and its fishing rights. Some 150 new monastic foundations were created between the 1360s and the early 16th century; the lasting establishment of monasticism throughout Russia dates from this period.

The expansion of Muscovy under Ivan III the Great

During the reign of Vasily II (1425–1462) it was decreed that the Grand Prince should be succeeded by his oldest son. Ivan III (1462–1505) continued to "gather the Russian lands," annexing the principalities of Rostov (1474), Novgorod (1478), and Tver (1485). In 1480, he resisted the powerful forces of Akhmat Khan (a descendant of Genghis Khan) with the "Great Standing on the Ugra river," thereby putting an end to Russia's subordination to the Golden Horde. From 1485, Ivan III proclaimed himself "Ruler of all Rus'," and the word "autocrat" came into use. He organized the first Russian coronation for his grandson Dmitry in 1498, with a ceremony modeled on the investiture of an heir to the Byzantine throne. Muscovy also opened to the West: in 1472, Ivan III married the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, Zoe-Sophia Palaiologina, a Greek princess with an Italian education; the Italian architects Aristotele Fioravanti, Alvise Nuovi, Marco Ruffo, and Pietro Antonio Solari contributed to the reconstruction of the Kremlin; and Ivan III contracted an alliance with Moldavia and forged links with the Habsburgs (the double-headed eagle, first represented on a Russian seal in 1497, actually came from Austria). Yet Russia's Orthodox identity was strengthened, rather than weakened, by these alliances with the West.

Moscow: the Kremlin armory workshops

The reign of Ivan III (1462–1505) witnessed the spectacular development of the Kremlin workshops, whose production reached its height under Ivan IV the Terrible (1533–1584). From the late 15th century onward, the best Russian artists worked there together with Western European coin makers, gunsmiths, and metalworkers—especially the highly esteemed artisans of Germany, England, and the Netherlands. All worked for the greater glory of the Tsar and Church. This engendered an extraordinary courtly art that married tradition with the technical and decorative innovations of the Renaissance. Inspired by Western European engraving techniques, metalworkers began to use cloisonné enamel and niello on gold, but were also attracted to the Oriental arabesque. Under the influence of Dionysius and his followers, the artists of the Moscow school modified the Byzantine tradition from the late 15th century onward, while the Kremlin workshops were quick to develop their own distinctive iconography with its complex, elegant, sometimes Mannerist style. In the second half of the 16th century, their art spread as far as the outer reaches of Muscovy.