Artists and collectors

As we have already seen, portraiture enjoyed a particular status in Venice; moreover, the Venetians accorded a quite specific place to the representation of artworks and artists, as is borne out by the many portraits of collectors surrounded by the works in their collections. Titian’s Portrait of Jacopo Strada was an opportunity to showcase his talent, in its movement, contrapposto, intensity, interplay of materials, colors, and contrasts providing a “lesson in painting.”

The Venetians had a real infatuation for portraits of artists; many collectors and artists themselves would commission portraits of painters, sculptors, and architects. In the main, the painters preferred to paint their own portraits, thus providing the opportunity for self-celebration or, rather, intimate reflection.

It was Titian who produced the most self-portraits throughout his life. His was a reflection not only on his creative relation with the heavens and his divine inspiration, but also on his awareness of the work involved and the difficulty of his toil, with a real hope for fame that would transcend death.

While Titian favored three-quarter portraits, Tintoretto preferred to paint himself in front view. Throughout his career he sought to shock and flaunt his difference as compared with other artists. In this chosen course, we cannot ignore the parallel with representations of the Holy Face or Christ the Redeemer, a comparison that he exploited to the full—looking not at the spectator but looking inwardly, in his search for inspiration.

Learn more+

Titian

, Jacopo Strada

Learn more+

Titian

, Jacopo Strada

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

(Inv GG-81)

Learn more+

Titian

, Self-Portrait

Learn more+

Titian

, Self-Portrait

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

(Inv P00407)

Learn more+

Tintoretto

, Self-Portrait

Learn more+

Tintoretto

, Self-Portrait

Paris, Musée du Louvre

(Inv 572)

Learn more+

Veronese

, Alessandro Vittoria

Learn more+

Veronese

, Alessandro Vittoria

New York, Metropolitan Museum

(Inv 46.31)

Learn more+

Palma Giovane (Palma the Younger)

, Portrait of a Collector

Learn more+

Palma Giovane (Palma the Younger)

, Portrait of a Collector

Birmingham, City Museum & Art Gallery

(Inv 1961P48)

Close x

Titian, Jacopo Strada

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

(Inv GG-81)

This is probably the most striking portrait of this latter half of the sixteenth century. With his luxurious garments, jewelry, and weaponry, Strada has all the trappings of high society. The objects depicted around him are indicative of the figure's intellectual pursuits—ancient coins, books, and sculptures. Strada has taken hold of a statuette with a sensual flourish as if offering it to someone who is with him. The aim is rather to show a passionate and energetic figure than a dilettante highbrow.

© Kunsthistorisches Museum , Vienna

Click on the picture to zoom: Jacopo Strada (new window)

Close x

Titian, Self-Portrait

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

(Inv P00407)

Titian has painted himself in profile, an archaic posture then reserved for deceased figures or illustrious men that the painter was supposed to represent without having seen them. He is thereby orchestrating his own glory. In accordance with his profession, Titian has depicted himself holding an implement in his right hand. Yet he lets mystery hang over the object's nature—brush, quill, or stylus—thus allowing him to play on the relationship between the two activities of painting and writing, and to emphasize the painter's intellectual side.

© Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Click on the picture to zoom: Self-Portrait (new window)

Close x

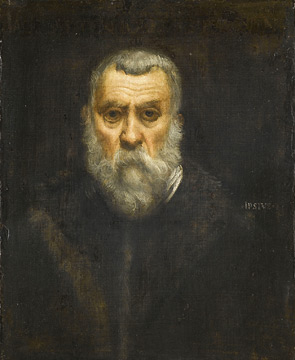

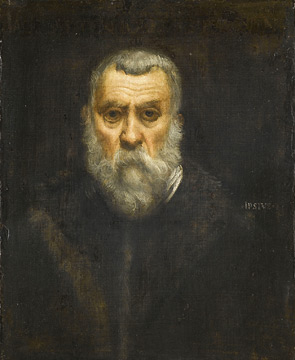

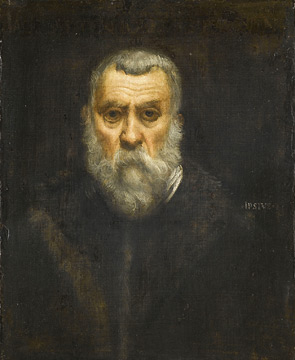

Tintoretto, Self-Portrait

Paris, Musée du Louvre

(Inv 572)

This Self-Portrait was supposed to join the collection of portraits and self-portraits of artists built up by Hans Jakob König, a German art dealer and goldsmith settled in Venice. In order to stand out among this artistic pantheon, Tintoretto chose to paint himself in frontal view. This strict angle was intended to catch the eye, to arouse interest, and to give an inkling of the painter's spirit while at the same time referring to the frontal representation of a "Christ of Pity." Tintoretto did not hesitate to portray himself with all the morbidity of old age. As death was drawing nearer, only an image was now able to record his dreams of eternity.

© RMN / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Click on the picture to zoom: Self-Portrait (new window)

Close x

Veronese, Alessandro Vittoria

New York, Metropolitan Museum

(Inv 46.31)

The sculptor Alessandro Vittoria is depicted in a half-length portrait, his bust in three-quarter view, and his head turned to face the viewer, behind a table covered with an oriental carpet. On the table are two sculptures; though he turns his back on that of an "antique" torso, he is embracing a plaster modello used in the creation of his Saint Sebastian. Vittoria was particularly proud of this latter work that Veronese delights in depicting in detail—the contrapposto, grace of movement, and the taut muscle structure heightened by the raised arm.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Click on the picture to zoom: Alessandro Vittoria (new window)

Close x

Palma Giovane (Palma the Younger), Portrait of a Collector

Birmingham, City Museum & Art Gallery

(Inv 1961P48)

While Vittoria's statuette of Saint Sebastian appears in this portrait by Palma Giovane (Palma the Younger) alongside four antique copies, Alessandro Vittoria is unrecognizable in the figure depicted. It has been thought to be a portrait of the collector Bartolomeo della Nave who had purchased a copy of the Saint Sebastian, though in bronze. Given the figure's bearing and what he is holding in his hands, it may be the portrait of an artist.

© Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Click on the picture to zoom: Portrait of a Collector (new window)